Twitter Summary: Great ideas are uncovered when we disengage ourselves from our work and intentionally let our minds wander.

Principle

So far I’ve shared a few posts touching on David Burkus’ book The Myths of Creativity. Today I want to share a bit about what Burkus calls The Eureka Myth.

Burkus writes that many of us subscribe to “the notion that all creative ideas arrive in a ‘eureka’ moment…we conveniently gloss over the tireless concentration that came before the insight, or the hard work of developing the idea that will come afterward.”

The reality is that most great ideas that appear to come from a flash of inspiration are actually part of a larger process that culminates in that moment. Burkus cites Henri Poncaire who explained the creative process as having the following phases: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification. The eureka moment usually falls under the illumination phase, but could never occur without preparation, doing the hard work, and incubation, taking a break to focus on something unrelated.

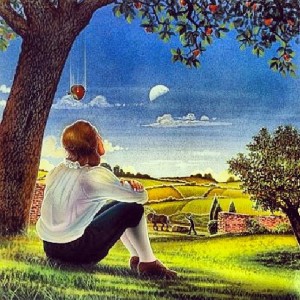

The falling apple would have had no significance if Newton had not prepared himself for it with constant curiosity and study. Without that, it would have just been a falling apple.

Burkus highlights research that demonstrates “incubation periods, even those as brief as a few minutes, can significantly boost a person’s creative output” and “incubation periods which allow the mind to wander offer a significantly stronger boost to creativity, suggesting that individuals whose minds regularly wander may be more creative in general. Such mind-wanderers appear to have tapped into the power of incubation.”

Stories of Isaac Newton getting hit with an apple or Archimedes sitting in his tub present a false sense of authority to the eureka myth. Neither of these instances would have produced the same result if both Newton and Archimedes had not been diligently engaged in the preparation phase, in other words, if they had not been constantly working towards finding a solution. No amount of sitting under trees or in bathtubs will solve your problems. So in essence, the story of Newton and the apple is BS because it rarely is told in a way that captures the entirety of the process before the apple fell, leading to his great idea.

Ultimately, great ideas are uncovered when we disengage ourselves from our work and intentionally let our minds wander. That is how we unleash the power of creativity through incubation. Take a break, take a walk, play a game, or whatever. Let the ideas simmer in the back of your mind while you enjoy some unrelated activity. It is in that moment of mind-wandering that we often make amazing connections to things that may seem unrelated, but have profound applications.

Creativity Through Incubation and Making Connections

In the book The Element that I wrote about previously, Ken Robinson tells the story of physicist and Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman. Feynman was a promising university student who was having lunch one day when he saw a plate go flying in the cafeteria with a blue medallion in the center of it. He noticed the medallion spinning faster than the outer edges of the plate. That caused him to take some notes on a napkin in relation to studies Feynman was previously engaged with and he continued to toy with those ideas for years. That equation that was casually written on a napkin turned out to be worthy of the Nobel Prize years later.

If Feynman hadn’t been preparing for that moment by diligently studying, that plate would have just been another event in his life that had no meaning. However, because of the diligent work he had been engaged in and the time he had taken to disengage from that work for a moment, Feynman was able to make an amazing connection between an otherwise normal event and his studies. It wasn’t a eureka moment. Feynman had worked hard and prepared himself to be deserving of an idea that sprang from an event that seemed unremarkable to everyone else present.

How many of us would have seen the value of a spinning plate or a falling apple or an overflowing tub? No one would have if it weren’t for hard work and someone probably saying, “I nee to take a break.”

My personal connection is a story that happens far too often. I’ll get together with other musicians to work on new music, we have some great ideas, but nothing clicks in that moment. We try hard to throw everything we have at the problem, but nothing sticks. Hours later, we leave frustrated and disappointed we couldn’t force out greatness.

And then the next day, getting in the car to go get some gas or groceries, the radio turns on and my mind starts producing amazing ideas that seem like gold. I’m banging out great rhythms on my steering wheel that would have been perfect for our new song, hum amazing melodies that would work great for horns or vocals. I usually don’t anticipate these ideas so I have to pull over to try and capture some of it before it slips from my mind. Usually, I lose all of it and have to resign myself to being teased by the gods of creativity.

I realize that these moments are exactly the same as Newton and Feynman. It is when you disengage yourself from problems, decide to relax and enjoy some other activity, that you seem to find great new solutions and options.

So What?

Do you have a story of a time where you took a break and come to a great solution? I’m guilty of trying to force out great ideas when solutions become stalled.

Recognize the power of incubation. Be okay with taking a break, you’re not wasting time, it’s a big part of the creative process. Take more breaks, incubate, and let the great ideas present themselves.

Next Weeks Post: Next week I’m going to write a bit about the cohesive myth, explaining how conflict is necessary for great ideas.

Leave a reply